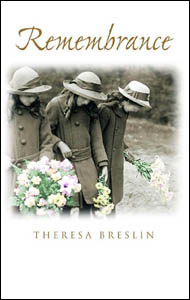

Remembrance by Theresa

Breslin (Doubleday, 2002)

ISBN 0 385

60204 9

42

chapters; 304 pages

Subjects:

World War One, England, France, nurses, pacifism, letters, war poets, young

adult fiction (Year 9-12)

Synopsis:

This is a story of those who go off to war and those who stay

behind. It shows the impact that World War One had on small communities, on the class system in Britain and on the place of women in

society.

The story is told through the eyes, lives and experiences of

five young people living on opposite sides of the class barrier in a small

Scottish village. At the start of the book, in October 1915, they are aged from

14 to 22. On one side are the children of the local shop: John Malcolm, who can’t wait to join the war,

his twin Maggie and younger brother Alex, who also manages to sign up despite

being well under age. At the “Big House”, Francis struggles to know how far he

should follow his pacifist leanings, while his younger sister, Charlotte, wants

to trains as a nurse.

You know as a reader that their lives are going to change, and it’s

unlikely they will all survive unscathed. As they start to go their different

ways, some of the story is told through letters, using a change in font for

each letter-writer. This works well except for Francis’ letters which use an

italic font that is harder to read.

Theresa

Breslin has obviously carried out a huge amount of research to be able to

portray such a variety of scenes: a military tribunal hearing, the munitions

factory where Maggie works, the hospitals, the front line. There are some

moving moments, such as when telegrams get delivered all over the village after

a big battle (“up and down the lanes, lots of doors got chapped this

afternoon.”)

Extracts

from poems of Siegfried Sassoon (Suicide in the trenches and Aftermath) appear

at the beginning and end of the book.

You can read an extract from the book here.

"Charlotte has been working at the local cottage hospital but has now been accepted to the military hospital in the city. On her first day a hospital train full of casualties arrives, and despite being already crowded, the hospital must take them. Although she is only 16 and has very little experience she must help in the emergency."

You can read an extract from the book here.

"Charlotte has been working at the local cottage hospital but has now been accepted to the military hospital in the city. On her first day a hospital train full of casualties arrives, and despite being already crowded, the hospital must take them. Although she is only 16 and has very little experience she must help in the emergency."

|

| Another cover of the same title |

Teachers notes can be found here and here.

“Wars aren’t simply about those fighting at the fronts. Wars are also about those continuing to live in homes from which father and sons, husbands and sweethearts have gone, some never to return. World War I provided an opportunity for some women to work out with the home for the first time in their lives, giving them a sense of independence they might never otherwise have had. It also made people question the way they lived their lives, the way they expressed themselves and the way the interacted with other people.”

Questions:

Theresa Breslin herself poses a series of questions for readers of this book on her website. These are some of them:

This review in Publishers weekly says the book "starts slowly but ultimately packs a wallop." Another review on the blog Not acting my age (books written for teens) describes it as "a lively way to view a world of nearly a century ago" but wonders if it is more of an adventure story than a truly YA book as (this blogger feels) the characters don't undergo much emotional growth.

Author’s website

Theresa Breslin herself poses a series of questions for readers of this book on her website. These are some of them:

- How do you react when the country is swept by war fever? Would you forge the date on your birth certificate and run away from home?

- What if you don't believe in the senseless slaughter of young men in the name of politics and empire - what do you do when others label you a coward?

- In a world where women have few rights... would you have the strength to use the opportunity of war to stretch your mind and grasp the possibilities that it opens up? Could you leave the safety of your family and challenge the way the world works?

- How can love survive in the horrific conditions of loss and bereavement that a world war results in?

This review in Publishers weekly says the book "starts slowly but ultimately packs a wallop." Another review on the blog Not acting my age (books written for teens) describes it as "a lively way to view a world of nearly a century ago" but wonders if it is more of an adventure story than a truly YA book as (this blogger feels) the characters don't undergo much emotional growth.

Author’s website

I didn’t

know anything about Theresa Breslin before, but her website says she was

born and brought up in a small town in Scotland, worked as a mobile librarian, has

written over 30 books for children and young adults and won the Carnegie Medal

for Whispers in the graveyard (1994) about

a dyslexic boy. You can read an interview with her here. I like the bit where she says the most important quality for a writer is "tenacity".

She has said about this book:

She has said about this book:

"At this time of a new century I thought it was important to write this

book. I wanted to show the many and complex aspects of war. The soldier who

firmly believes he is doing his duty and is prepared to sacrifice his life to

protect his family. The soldier, disillusioned, who feels his very soul is

being corrupted by contact with militarism. The girls who went to nurse, wanting to help the war effort or looking

for adventure, and finding in some cases a self-fulfilment they never would

have had if the war had not occurred. And… the terrible grief of those left

behind."

She also has a

page that I found very interesting on the research she carried out in libraries, archives, museums, newspapers and private family papers, and in her own visits to the battle sites in France and Belgium.

Other books you might like:

The role of women in World War One, and the impact that war had on them,was undervalued or unacknowledged for a long time, so it's good to see books like this. Jackie French is another author who has tackled the topic in A

rose for the Anzac boys (Harper Collins, 2008).

Things I didn’t know

I knew that letters from the Front could be censored, and soldiers would try to find ways around the censorship to hint at their whereabouts - perhaps using some kind of riddle, or a phrase that might mean something to the recipient, but I didn't know about the codes they used. At one stage, Francis sends a letter to Maggie which she doesn't fully understand until Alex explains it to her, saying “lots of soldiers send coded messages in their letters. They sometimes use it to tell their families know whereabouts in France they are.” The code might be a nonsense phrase, or words that don’t make sense in the context of their

surroundings. For example, “nineteen shillings and nine pence, or rather not” would indicate a

word that was 19 lines down and 9 words across.

Theresa Breslin says in the notes on her research that she found out about this when she was "privileged to be allowed to read through some family papers which contained letters from a young soldier who was killed on the Somme."

Theresa Breslin says in the notes on her research that she found out about this when she was "privileged to be allowed to read through some family papers which contained letters from a young soldier who was killed on the Somme."

I'd never heard of The Bantams (the battalion that young Alex hopes to join.) At the start of the war, the minimum height requirement for volunteers was 5 ft 3 inches, but many men who were shorter than that still wanted to join up. You can read about them here and here, and this site describes the Canadian Bantams. This 25 second, silent newsreel clip from British Pathé shows a military review of the Bantam Battalion, including (as the notes explain) one "extremely short soldier".

|

| Library of Congress: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3g10942/?co=wwipos |

No comments:

Post a Comment