The horses didn’t come home by Pamela Rushby (Angus & Robertson, 2012)

Cover sub

title: A young soldier and his horse in the Battle of Beersheba.

250 pages; chapters told alternately by Harry and Laura

250 pages; chapters told alternately by Harry and Laura

Subjects:

World War One, Middle East, Egypt, Palestine, Beersheba, Australia, Banjo Paterson, archaeology,

horses, animals, junior fiction (Year 5-8)

Synopsis

From the blurb on the

back:

“The last great

cavalry charge in history took place at Beersheba in the Sinai Desert in 1917.

It was Australian soldiers and horses that took part in, and won, this amazing,

unexpected, unorthodox victory. The men proudly claimed it was their

great-hearted horses that won the day. But in the end, the horses didn′t come

home...”

The book starts with

a lovely evocation of the Australian outback. Harry and his friend Jack, aged

16, have just finished school and are returning home. Harry is glad to be going back to his beloved

horses, but Jack is restless, aware that there is a war going on. Then the army

officers arrive, looking for horses to buy, and soon Harry and Jack are off to

war as well with the Australian Light Horse.

Like many other books

about war, this one stresses the importance of letters, both to those serving

and to those waiting back at home. Harry’s letters to Laura at boarding school, pretending to come from Bunty (the horse) are a delight, and Bunty is a very real character in herself. There are some lovely moments of humour, in

particular the time when the Aussie soldiers talk in Aboriginal placenames to

confuse the English officers who are speaking French in front of them, and when

they discover that the same nurse has agreed to write to them all, after they'd each thought they had some special understanding with her.

If you know what

happened to the horses, you will understand the Prologue as you read it. If

not, it will become clear at the end.

One good thing to come out of this was

the founding of the Old War Horse Memorial Hospital in Cairo, in 1934, which

led to the work of the Brooke animal welfare organisation. A woman called Dorothy Brooke had discovered how badly many old British war horses were being treated and this is the text of the letter that she wrote in 1931, alerting the public to their plight.

An added level of interest (pun unintended, but apt) comes from Jack’s fascination with archaeology and the stories of ancient Egypt. During one period of leave, they travel to Luxor and go to see the Valley of the Kings. In the middle of the desert they find a man sitting at a folding table under a white bell tent. This is Mr Carter, “Supervisor of Excavations for Lord Carnarvon”. In November 1922, he would discover the undisturbed, nearly intact tomb of the Pharaoh Tutankhamen.

|

| In the late 1800's Howard Carter like many others went to Egypt to discover lost tombs and treasures from the past. With the backing of wealthy folk from back home we was able to spend years (literally 30+) searching for undiscovered tombs. |

The book also

mentions the uncovering of the Byzantine Shellal Mosaic which is now on display in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. This article in the Sydney morning herald poses the question: Was

it looted? Should it be returned?

Author’s website

Pamela Rushby was born in Toowoomba, Queensland, and now lives in Brisbane. Here she talks about the book, the history behind it and what inspired her to write it.

Teacher’s guide is available here.

Teacher’s guide is available here.

Other books you might like:

Charlie and Tommo

in Private Peaceful sign up at nearly

16, so does William in My mother’s eyes: the story of a boy

soldier, and Sydney

in One boy’s war. The boys in War game are very young as well. “Boy soldiers” by Norman Bilbrough in School Journal, Part 4, No 3, 2008 tells

the story of two young New Zealand soldiers, Stan Stanfield and Len Coley, who fought in

World War One.

Light Horse Boy by Dianne Wolfer also tells the story of the Australian Light Horse.

NZ connections:

In Egypt, Harry

meets a couple of Kiwi soldiers from the NZ Mounted Rifles, Frank and Ollie. To

start with, they make fun of each other’s uniforms - the New Zealanders’ “baggy

trousers and floppy hats”; the “kangaroo feathers” (actually emu feathers) that

the Aussie soldiers wear in their hats - but they soon become good mates, and

keep bumping into each other throughout the book.

New Zealand horses have also played an important role in war. On pg 32 of Anzac Day: the New Zealand story, you can read about Bess, one of 11,000 horses that went overseas with the NZ

troops, and one of only four that returned. There is a memorial to her at Bulls (on private property, but it can be seen from the road.)

|

| 'Memorial to Bess the horse', URL: http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/media/photo/memorial-bess-horse, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 19-Sep-2013 |

Things I didn’t know

I’d heard about the Australian horses used in the First World War, but after reading the explanation on pg 11, I finally understand why they were called walers. According to Laura’s father, their ancestry can be traced back to seven horses (one stallion, five mares and one colt) that arrived with the First Fleet. These bred with other horses that came later: “English thoroughbreds, sturdy Timor ponies, and even Arabs”, to produce a new sort of horse suited to life in Australia. The horses were strong and fast, light and medium-sized, of any colour, and they were called walers because they were first bred in New South Wales.

I didn't know about the charge of the Light Horse at the Battle of Beersheba. On the NZ Historyonline website, this is referred to as part of the Third Battle of Gaza.

I’d heard about the Australian horses used in the First World War, but after reading the explanation on pg 11, I finally understand why they were called walers. According to Laura’s father, their ancestry can be traced back to seven horses (one stallion, five mares and one colt) that arrived with the First Fleet. These bred with other horses that came later: “English thoroughbreds, sturdy Timor ponies, and even Arabs”, to produce a new sort of horse suited to life in Australia. The horses were strong and fast, light and medium-sized, of any colour, and they were called walers because they were first bred in New South Wales.

I didn't know about the charge of the Light Horse at the Battle of Beersheba. On the NZ Historyonline website, this is referred to as part of the Third Battle of Gaza.

|

| Australian Light Horse going into action. Photograph taken by Francis Gillard Rathkey. |

In October 2012, the famous charge was re-enacted by members of the Australian Light Horse Association. You can watch the re-enactment on Youtube here.

Here you can read about a bugle

that was used at the Battle of Beersheba. It belonged to Roy Wynter, aged 18, a

bugler and signalman. He was born on a Taree dairy farm in 1899, and enlisted

in the 12th Light Horse Regiment at the age of 16, following his brother to

war. Wynter also worked alongside Banjo Paterson tending the horses.

War poetry

Banjo (Andrew Barton) Paterson (1864-1941) was a famous

Australian bushman, journalist and poet. The

man from Snowy River is one of his most well-known poems, and he also wrote

Waltzing Matilda. He worked as a war

correspondent in the South African War, and sailed for England when World War

One broke out, hoping to do the same again.

Instead, he ended up driving ambulances, then later was commissioned in the 2nd Remount Unit of the AIF. (Remounts were war horses that weren't individually owned, but were supplied to soldiers who had lost their own horses.) He served in the Middle East, was promoted and commended the commanded the Australian Remount Squadron until 1919.

Instead, he ended up driving ambulances, then later was commissioned in the 2nd Remount Unit of the AIF. (Remounts were war horses that weren't individually owned, but were supplied to soldiers who had lost their own horses.) He served in the Middle East, was promoted and commended the commanded the Australian Remount Squadron until 1919.

I looked for any war poems that he might have written and came

across one called “We’re all Australians now,” published as “an Open Letter to

the troops at the Dardanelles” in 1915. But the one I found most moving was this one, first published in The

Kia-ora Coo-ee, 15 May 1918; and later in Aussie: The Australian Soldiers

Magazine, 15 April 1920.

Moving On

In this war we’re always moving,

Moving on;

When we make a friend another friend has gone;

Should a woman’s kindly face

Make us welcome for a space,

Then it’s boot and saddle, boys, we’re

Moving on.

In the hospitals they’re moving,

Moving on;

They’re here today, tomorrow they are gone;

When the bravest and the best

Of the boys you know “go west”,

Then you’re choking down your tears and

Moving on.

In this war we’re always moving,

Moving on;

When we make a friend another friend has gone;

Should a woman’s kindly face

Make us welcome for a space,

Then it’s boot and saddle, boys, we’re

Moving on.

In the hospitals they’re moving,

Moving on;

They’re here today, tomorrow they are gone;

When the bravest and the best

Of the boys you know “go west”,

Then you’re choking down your tears and

Moving on.

|

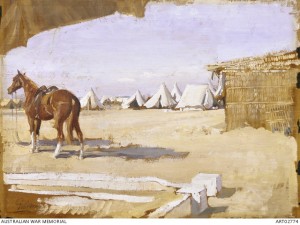

| View from Major ‘Banjo’ Paterson’s tent, Remount Camp at Moascar, North Egypt, 1918 George Lambert |